We went to have a look around the museum where you can explore how the port, its people and their creative and sporting history have shaped the city.

The museum opened on 19 July 2011 in a purpose-built landmark building on Liverpool’s famous waterfront. The design concept for the building was developed by Danish architect 3XN and Manchester-based architect AEW were later commissioned to deliver the detailed design. It has won many awards, including the Council of Europe Museum Prize for 2013.

The Museum of Liverpool replaced the older Museum of Liverpool Life which closed in 2006. The original museum was housed in the old Pilotage and Salvage Association buildings on Liverpool’s waterfront, in between the Albert Dock and Pier Head. The new modern designed building now houses most of the original museum’s exhibits on a site close by.

National Museums Liverpool (who run seven facilities across Merseyside including the Museum of Liverpool) say that is the largest newly-built national museum in the UK for more than 100 years. The Museum quote a range of interesting facts about the building.

It occupies an area 110 metres long by 60 metres wide and at its tallest point it is 26 metres high and that makes it longer than the pitches at either Anfield or Goodison Park, more than twice as wide as the Titanic, and as tall as five Liver Building Liver birds placed end to end.

The museum’s frame is constructed with 2,100 tonnes of steel – equivalent to 270 double decker buses. The 1,500 square metres of glazing offer striking views of the city, especially from the 8 metres high by 28 metres wide picture windows at each end of the building. The museum is clad in 5,700 square metres of natural Jura stone, which if laid out flat would cover a football pitch. 7,500 cubic metres of concrete and 20 tonnes of bolts have been used in the construction. And 20,000 cubic metres of soil – equivalent to eight Olympic swimming pools – have been excavated from the site.

It is certainly a strikingly modern building.

The Museum displays are divided into four main themes:

- The Great Port,

- Global City,

- People’s Republic, and

- Wondrous Place

These are located in four large gallery spaces over three floors. On the ground floor, displays look at the city’s urban and technological evolution which includes the Industrial Revolution and the changes in the British Empire, and how these changes have impacted the city’s economic development.

The second floor looks at Liverpool’s strong identity through examining the social history of the city, from settlement in the area from Neolithic times to the present day, migration, and the various communities and cultures which contribute to the city’s diversity.

There are many highlights. I’ve noted some of these below.

Ben Johnson was commissioned to create The Liverpool Cityscape for the Capital of Culture year in 2008. He started the painting in 2005 and completed it during a public residency at the Walker Art Gallery in early 2008. It was originally displayed at the Walker as part of the exhibition ‘Ben Johnson’s Liverpool Cityscape 2008’ before moving to its permanent home in the Museum of Liverpool’s Skylight gallery.

The Liverpool Overhead Railway gallery tells the remarkable story of the first electric elevated railway in the world. The Overhead Railway was built in 1893 to ease congestion along seven miles of Liverpool’s docks. It was known as the ‘dockers’ umbrella’ as it also provided shelter from the rain. In the gallery you can climb into a carriage, which is fixed at the exact height of the original railway at 4.8m (16 feet) above the ground. The railway was eventually pulled down in the late 1950s.

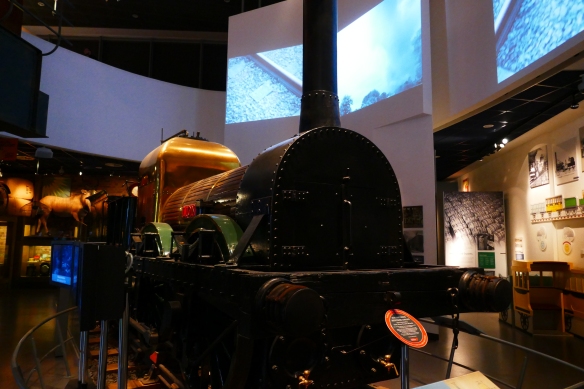

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway ‘Lion’ is an early steam locomotive which is on display in the Great Port exhibition on the ground floor of the Museum. In 2007 Lion, was moved by road from Manchester to Liverpool after being on loan to Manchester while the new museum was under construction. Some conservation work took place prior to it taking pride of place in the new museum. It starred three films the most notable being the 1953 film ‘The Titfield Thunderbolt’.

There is an enormous model of Sir Edwin Lutyens’ 1930’s design for Liverpool’s Catholic Cathedral in the museum. It is one of the most elaborate architectural models ever built in Britain. It represents the ambitious plan to build the world’s second largest cathedral, and it would have had the world’s largest dome, with a diameter of 168 feet (51 m). It was however far too costly and was abandoned with only the crypt complete. Eventually the present more modern Cathedral was designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd with construction starting in 1962 with completion in less than five years in1967.

There are a range of exhibits displaying Liverpool Life over the ages. The social and community history collections include objects of local, national and international importance reflecting the changing history of the city and the diverse stories and experiences of Liverpool people. They include popular culture and entertainment, working life, labour history, politics and public health. The museum also has a large collection of oral history interviews and filmed video histories from local people with stories to tell.

Football is an important aspect of life in Liverpool. Liverpool Football Club Museum and The Everton Collection have both lent the museum an array of memorabilia. And there are exhibits from Merseyside’s other team Tranmere Rovers.

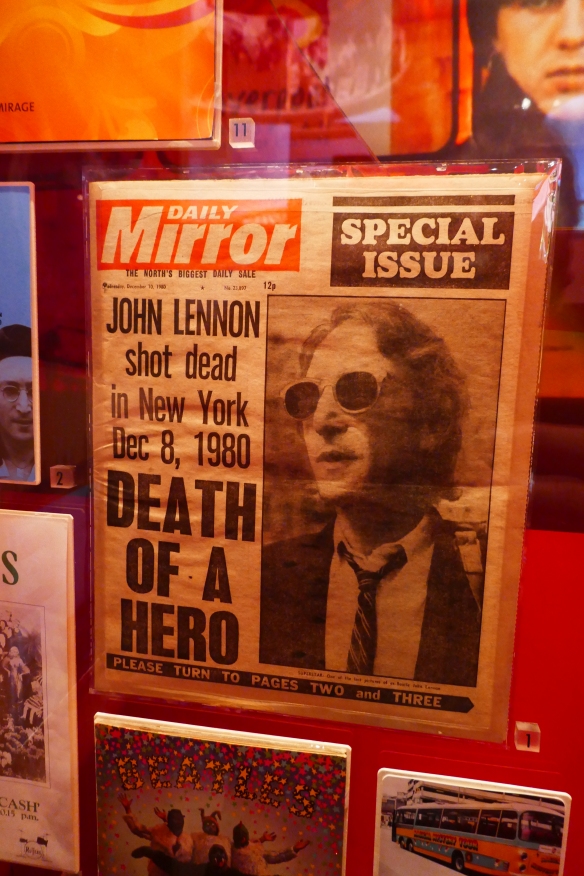

Whilst ‘The Beatles Story’ museum elsewhere in the Albert Dock has a large display to experience, the Beatles show at the Museum of Liverpool tells part of the story of the Fab Four in Liverpool which was the birthplace of a musical and cultural revolution that swept the globe.

At the time of our visit there was a special exhibition showing local music legends Gerry and the Pacemakers.

I took a number of images from the day, but there is much to see and experience and it will be worth re-visiting the museum to take it all in.